Resumen

Essay submitted for the History & Theory course MArchUD 2013, Professor Ross Exo Adams. An analysis of the peripheral urbanisation of Tangier through non regulated housing allows to critique governmental responses as well as to make a reading of the concept of territory. Research undertaken in London and Morocco during the years 2012-2013, while in the MArch Urban Design programme at Bartlett UCL.

Palabras clave

Actores

Nicole Rochette (Archipiélago), Author

All images are author’s own unless stated otherwise.

Cifras

Año

2013

The extent of some contemporary urban phenomena defies fixed conceptions of territory: urbanity appears to constantly surpass boundaries, and this fragility of definitions evidences the need to understand events at a larger – territorial – scale. Territorial in this sense calls for a concrete reading of a particular condition rather than an explanation of its constituents, something closer to an immanent than an external influence. Despite the evident relevance of political, economic and cultural analysis, territory has a physical component that is a concrete manifestation of itself and hence more suitable for examination.

Political theory lacks a sense of territory; territory lacks a political theory. Although a central term within political geography and international relations, the concept of territory has been under-examined”.

Elden, S., Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography. 34, 799-817. 2010. [Accessed 24 May 2013]; Available from: http://dro.dur. ac.uk/6850/1/6850.pdf. p. 1.

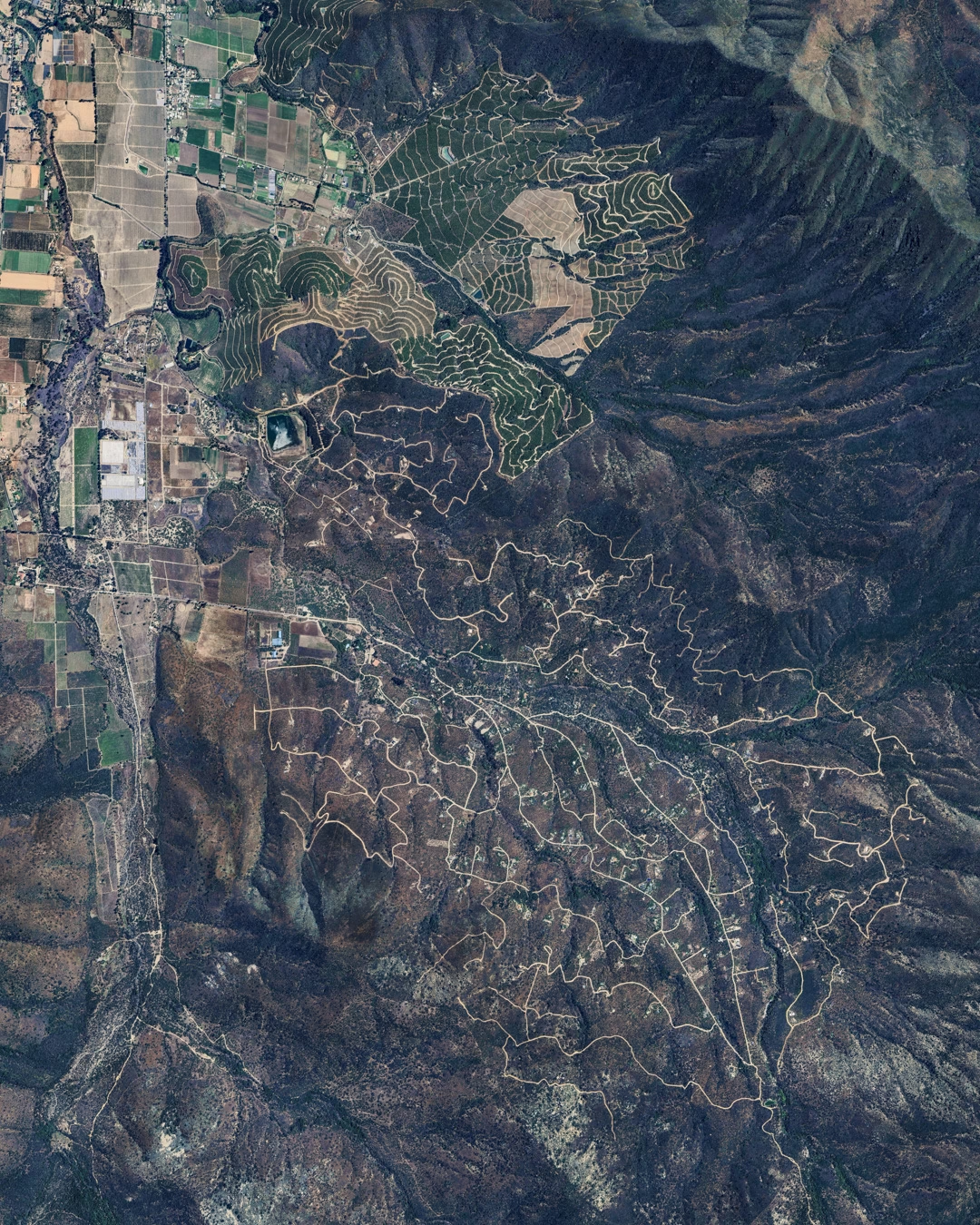

An interesting terrain of analysis is the situation that marginal territories present, territories which have not yet been effectively incorporated to the urban realm, and can then be better observed through their material reality. Phenomena such as the spread of housing in the city of Tangier (an example of what occurs in many other North African and Moroccan urban centres)[Image 1] allow us to read territory taking into consideration not only the traditional administrative and political aspects (and scales) but also the mechanisms and logics of production of territory that are made possible within specific physical contexts. The case of margin territories in Tangier allows us to read both the political and economic driven mechanisms through their direct relationship to land conditions. This text will attempt to demonstrate the importance of looking back at territory through its material manifestations.

Case study: Tangier, Morocco.

Migratory movements

The north of Morocco is both a place of immigration and emigration. Flows of migrants from sub Saharan Africa pass through Morocco2 in the hope of reaching Europe and when they are confronted with restrictive European borders are forced to stay in Morocco for a relatively long period. The relationship between the existing and the migrant population becomes then crucial, mainly when they attempt to settle more permanently in urban areas.3

2 de Haas, H. International migration and regional development in Morocco. Workshop New Moroccan Migrations, Institute of Development Studies, Sussex Centre for Migration Research, University of Sussex, 2005.

3“Once across the Sahara, the Subsaharian trans- migrants stick to the Maghrebi societies by grafting their own circulations on those of the local popula- tions. In Morocco, the populations who deal with the passing and the more or less durable settling of these newcomers are the ones living in socioeconomic relegation areas, such as the poorer suburbs of Rabat, Casablanca or Tangiers; these populations know what migration is about, as they are themselves the product of a continuous arrival of inland migrants”. Mehdi Alioua, Nouveaux et anciens espaces de cir- culation internationale au Maroc, Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée [Internet], 119- 120. 2007, online since 02 March 2012. [Accessed 24 May 2013]. Available from: http://remmm.revues. org/4113. Author’s translation from the French for all quotations of this text.

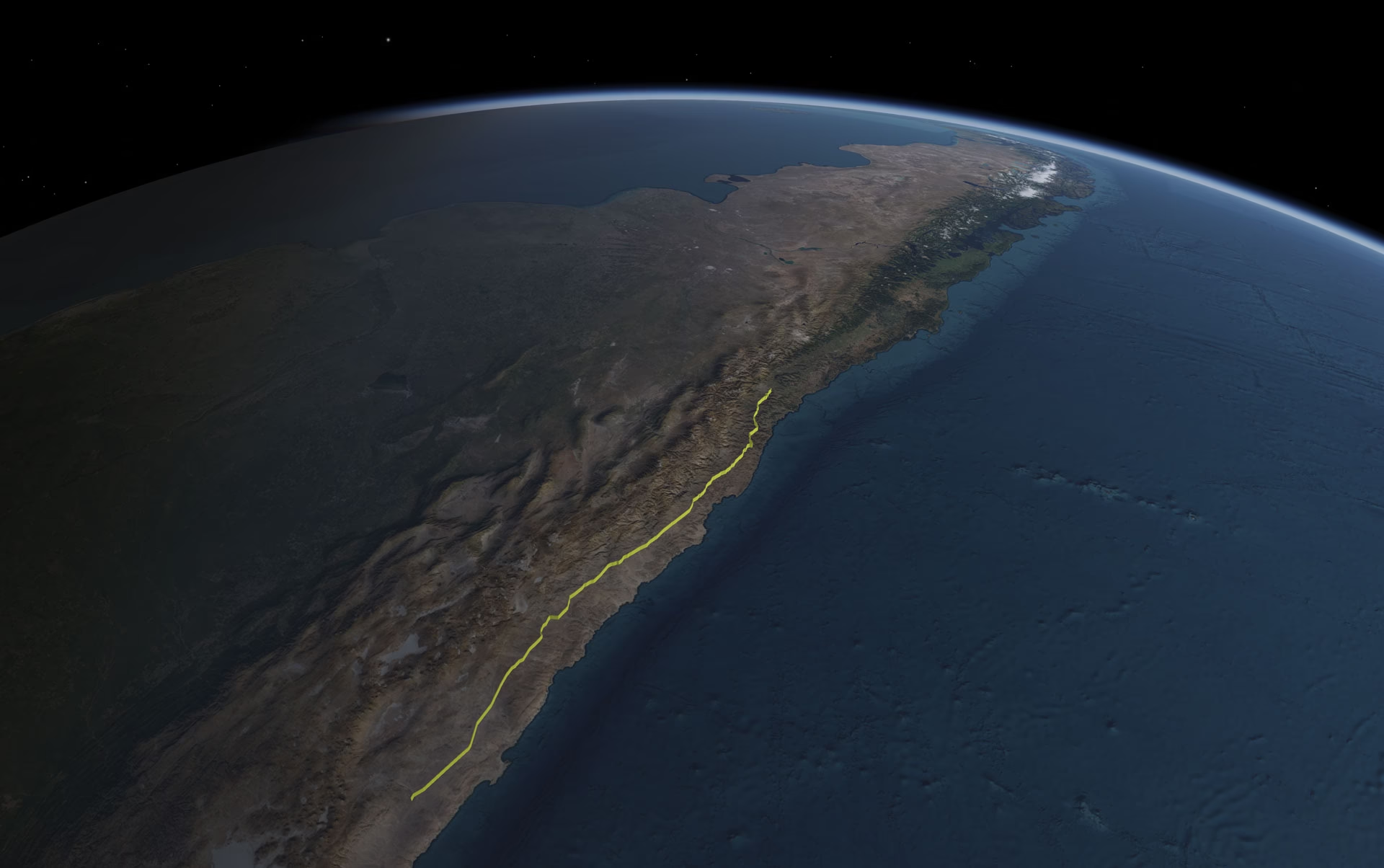

These international migratory movements are a significant cultural component of the growth of urban centres, yet they are less numerous than the internal migrations between rural and urban zones, attracted by the work available in the area. The Tangier-Tétouan region [Image 2] receives an important amount of rural migrants from its neighbouring regions [Image 3] , and is thus seen as a transit platform, where migration routes cross tourist itineraries and the exchange and circulation typical of a port city, making the region a place of confluence of people who are in transit. However in reality this results in an accelerated growth of the urban areas. Even migrants who are in transit in Morocco have a tendency to stay there for long periods of time, and the need for permanent residency is confronted with a saturated and degraded urban fabric and insufficient offer of adequate low-cost housing.4 The areas of the region which are still not urbanised come therefore into tension because of the forces that hover over it, and when the existing urban structures become surpassed by the demands, the territories outside of the urban realm become contested territories.

4Amzil, L., Debbi, F., and Le Tellier, J. La Mobilité Urbaine dans L’Agglomération de Tanger: Evolutions et Perspectives. Sophia Antipolis: Plan Bleu, 2009. p. 60. Author’s translation from the French for all quotations of this text.

Irregular expansion of Tangier

The city of Tangier is the main destination of migratory movements in the region, receiving around 40% of the migratory flux of the Region.5 However, “the region’s urban poles are not prepared to receive these populations. The cities are sprawling during the last years, mainly because of an excedentary migratory result. Since this movement is not accompanied by a planning of the building or services, it results in dysfunctions in employment, housing and infrastructures”.6 After Tangier lost its international status and was annexed to Morocco,7 the city expanded beyond the limits of the international period, while the relevance of migration in the urban growth of Tangier was 26 % during the 60s, 40 % during the 70s, 33 % during the 80s and 45 % during the 90s.8 The entire region observed an intense population growth 9 [Image 4, 5, 6] precisely while the city did not have any plans or orientations for the development. “The first sectorial urban orientations were launched starting in 1948 in face of the random development of Tangier. These plans were never approved but served as reference and have permitted to fill the void for the urban orientations for both the international and post-international administrations whenever they wanted to”.10

5Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix- Marseille University, 2006. p. 83. Author’s translation from the French for all quotations of this text.

6Ibid. p. 181

7Tangier was made an international zone in 1923 under the joint administration of France, Spain, and Great Britain, statute that was maintained until 1940. Between 1940 and 1945 however Tangier was incor- porated into the Spanish zone of Morocco but was then restored to its international status. Tangier loses its international statute in 1956 and is then joined to the Kingdom of Morocco.

8Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix- Marseille University, 2006. p. 128

9By 1960 the entire region had 811,517 inhabitants (RGPH 1960), which has grown to 2,460,220 in 2004 (RGPH 1960) and particularly the current Prefecture of Tangier (roughly corresponding to the limits of the international zone) grew from being a small medina with an initial development in 1942 into a city of 436,227 inhabitants in 1982 and then to 756,964 inhabitants in 2004 Haut-commissariat au Plan et direction de la Statistique. Recensement général de la population et de l’habitat, [Accessed 24 May 2013]; Available from: http://www.hcp.ma

10Bekkari, H. Tanger Post Internationale, article in Urban generations : post-colonial cities / ed. by David Richards, Taoufik Agoumy, Taeib Belghazi. – Rabat : Faculty of Letters of Rabat, 2005. – 471 p. : ill., krt. ; 24 cm. – (Publications de la Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Rabat Série: Colloques et sémi- naires, ISSN 1113-0377 ; 126). p. 273. Author’s trans- lation from the French for all quotations of this text.

This random expansion of the city refers not only to a lack of planning but mainly with a resulting uneven territory, a city that is heavily polarised between a compact centre and a dispersed periphery. The sense of dispersion is amplified by the topography: scattered pieces of the city attempt to function as a whole in what is an uneven piece of land, with infrastructures laboriously attempting to connect it and with a noticeable lack of basic services.

Within this scenario, a particular type of habitation appears especially marginalised and numerous. The most peripheral and hilly areas are covered with a blanket of single family housing units, with a visible homogeneity that contributes to the impression of something existentially different from the rest of the city. The constructions appear to be randomly placed over the ground, and together they form an impressive territory. [Image 7]

Territories in the margins: Non regulatory housing

The main component of the sprawl

The random development mentioned above refers to the increasing rate of construction of individual family units without referring to urban regulations, which were practically inexistent in Tangier for most of the city’s development period. In 1982 the first “Schemas Directeurs d’Amenagement d’urbanisme” for Morocco were realized by the group Huit, but the plans were not approved until 1993, for when the city of Tangier presented “a chaotic urban reality and the urbanism was already very oriented towards the clandestine habitation”.11 This phenomenon of clandestine habitation is referred to (among other less adequate terms) as Non-Regulatory Housing (NRH).12 Its advance dates back to the 1970s and presented a strong growth in the 80s and 90s. By 1981, this type of dwelling housed 10% of the urban population and by 1993, 286 ha were occupied by the NRH, which represented 17% of the urban area and 30% of the overall housing stock.13

These developments are located mainly around the south and south-east areas of the city: neighbourhoods such as Beni Makada, Bir Chifa, Moghogha, Sania, Tanja balia, etc. represent different relevant products of this process14[Image 8]. The direction that the urban growth took in absence of enforced regulations was heavily influenced by the terrain conditions in these areas. While the flat, secure and easier to develop areas closer to the coast were under stronger control, flood zones, steep terrains and agricultural areas[Image 9] were kept with a looser hand, which gave way to unrestricted construction. The architect Hanae Bekkari points out that “the Administration did not acquire the zones non ædificandi and the green areas that had been and still are the prey of speculators. These terrains [were] transformed in the Plans d’Amenagement into urbanisable areas or given away to the informal habitat, sold by little lots for people generally issued from rural exodus”.15

11Ibid.

12The significance of the various terminologies is discussed later on in the text.

13Amzil, L., Debbi, F., and Le Tellier, J. La Mobilité Urbaine dans L’Agglomération de Tanger: Evolutions et Perspectives. Sophia Antipolis: Plan Bleu, 2009. p. 67.

14The neighbourhoods or quartiers represent a social cohesion unit: “The majority of households buy their land individually, but families from the same village acquire large patches of land in the same area in order to reconstruct forms of family and clan in por- tions of the neighbourhood (derbs)”. Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006. p. 392. In most cases too, the oldest inhabit- ants, belonging to the ancient rural douars, have become an authority in the place.

15 Bekkari, H. Tanger Post Internationale, article in Urban generations : post-colonial cities / ed. by David Richards, Taoufik Agoumy, Taeib Belghazi. – Rabat : Faculty of Letters of Rabat, 2005. – 471 p. : ill., krt. ; 24 cm. -(Publications de la Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Rabat Série: Colloques et sémi- naires, ISSN 1113-0377 ; 126). p. 274.

Non regulatory conditions

The resulting growth was a collection of significantly populated neighbourhoods scattered around the city’s hills and former agricultural areas. The logic of addition of single family units into neighbourhoods created a condition where vast zones are dormitory areas, with a high dependency to the central parts of the city and without network services[Image 10]. These types of constructions are easily recognisable since they share a very particular typology: their typological homogeneity is based upon structural principles, economic logic, and space qualities, together with a common isolation condition and a particular legal framework.

Regarding their urban condition, they are given the appellation of “under equipped” neighbourhoods because of their lack of basic infrastructure. These areas are often dense and excessively tight, since for maximum profitability every bit of land is utilized for construction. This density of built form achieved without development plan hinders the introduction of the infrastructure equipment, which would require the destruction of houses prior to the installation of network services and roads. The absence or deficiency of network services (water, sanitation, electricity) gives these neighbourhoods the more frequent name of habitat insalubre (unhealthy habitat), which is commonly used by the Moroccan authorities. However, most inhabitants manage to make up for the deficient access to service networks by either connecting illegally to them or relying on open water sources and fountains. The lack of public facilities such as schools and clinics is however more persistent.

The designation of non regulatory has to do with a common “irregular” condition regarding existing urban laws. This is not only a legal issue: this particular form of access to urban land has significant effects in the resulting urban fabric and its configuration. The need to “secure” property promotes a fast building procedure, and this necessity explains the proliferation of uniform building techniques and housing typologies.

Morocco has a very low land registration rate and most plots of non regulatory buildings are not registered in the cadastre.16 The farmlands go through a process of illegal subdivision of property[Image 11], and the “mother” titles are fragmented into several individual plots that do not have property titles registered with the cadastre and land conservation services. In many cases, the mother terrains from which they were subdivided do not necessarily hold property titles either.17 Most dwellers do not hold a property title (moulkia), but many hold some kind of right to inhabit through actes adoulaires.18 This complex situation is aggravated by Morocco’s intricate land property system: the existence of private land, state property (terrains domaniaux), collective land (terrains communaux), and religious property (biens habous) without clear information regarding their individual domains or limits. The illegal dwellings are not built on state owned land but mostly on private land (unlike the bidonvilles or slums, which are frequently built over public terrains thus assuring that the State takes care of their relocation), and do not constitute illegal occupations, since have been granted permission to live there either through a contract or acte adoulaire. They are not imposing themselves nor occupying the land by force.

Finally, the buildings themselves hold and irregular status: the absence of a preceding building permit (or the attainment of one despite not complying with the requirements to do so) is accompanied with a subsequent transgression of other construction regulations when existing, such as footprint and height. Non-ædificandi areas are overlooked and as a result, most dwellings end up being built on what is considered to be non-buildable terrains. The outskirts of Tangier have a rugged topography [Image 12], and terrains with strong slopes (higher than 15% and 20%) leave gaps within the built fabric that are then filled up by occupants that take advantage of its state of neglect. Flood areas are also used for building, together with waterways, which summed up with strong slopes give way to dangerous landslides. The buildings’ transgressions are also regarding land use, since in some cases, areas designated for agriculture or infrastructure are sold for housing.

16Hyunjin, K. The Study and Example of application for the Establishment of Cadastral Methodology in Morocco. TS 5K – Cadastral Projects. FIG Congress 2010 Facing the Challenges -Building the Capacity. Sydney, Australia, 11-16 April 2010. [Accessed 24 May 2013]; Available from http://www.fig.net/pub/ fig2010/papers/ts05k%5Cts05k_kim_4150.pdf

17Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix- Marseille University, 2006. p. 128

18“A sale agreement, a domicile certificate and a certificate of construction are adoulaire acts that can be authenticated by the municipal services. These documents represent occupancy permits, a step in the long process of regularization of illegally purchased or tenure of land. They are not valid as property titles but they protect (in part) of a possible expulsion.” Le Tellier J., Ibid. p. 189

Restructuring procedures

Regarding the state’s approach towards this kind of development, from 1974 to 1975 the first organismes publics de l’habitat (OPH) were created, that later became organisms under the Ministry of Housing (OST). They were in charge of overseeing the restructuring of NRH and coordinating the various actors involved. In the non-regulatory areas, the direct interventions of the OST were of two types: restructuring procedures regarding equipment infrastructure such as sanitation and roads (water and electricity networks theoretically remain the responsibility of the owners), and land regularization.19 In 1984 a specialized agency called National Agency against Unhealthy Habitat (ANHI) was created. The ANHI from January 2004 joined the holding Al Omrane, whose two major objectives of their 2004-2007 quadrennial plan were doubling the production of social housing (especially the less expensive ones) and reducing the deficit in housing and equipment through a program for urban regeneration and improved infrastructure in rural communities.20

Tangier’s authorities in particular have recently carried out a series of changes over the urban legislation, attempting to contain the non-regulatory phenomena. This includes a modification of construction regulations in what they refer to as “rural centres”, allowing for a more dense built fabric in order to encourage rural population to stay in their douars (rural villages)21 instead of moving to the city, together with a study of a possible expansion of the urban limit,22 in order to contain the already dense built neighbourhoods.

The Moroccan programme “Villes sans bidonvilles” launched in 2004 also contemplated these kinds of developments within their objectives.23 However, unlike from the bidonvilles or slums, these dwellings are rarely subject to relocation procedures, since they are not built on state owned land but on legally acquired agricultural land, and have the quality of being solid brick buildings and spread widely enough to justify a different kind of action. In a beginning, as with slums, the inclination of state authorities was towards demolishing buildings that were outside the law (processus de relogement). However, this consequently burdened the state with the responsibility of providing a new dwelling to the families being evicted, and as the phenomena spread, this alternative would have evidently become economically non-viable.24

The alternative was to carry out in-situ restructurings. State programs attempt to introduce the lacking services gradually, however people are sometimes reluctant to start paying for them. Since the buildings are not legal, they are not subject to any type of taxation, and when regulatory campaigns are carried out, strict regulations are accompanied by the taxation of household (residential tax), which explains why the “regular” status is not necessarily sought for by the dwellers.25 Since the construction of homes precedes the urbanisation, the infrastructural layer of the neighbourhoods has to be introduced at a later stage. As mentioned before, this sometimes requires the demolition of some dwellings, and in most cases makes it impossible to serve all dwellings with road access or services. In the end, most restructuring procedures cannot attain complete servicing and are accompanied by the painting of facades and planting of vegetation to make the overall image change more dramatically.26 Being as it may, the resulting equipped areas are considered to be successfully “normalised” and added to the city’s urban realm.

Concerning their precarious legal condition, many plans “provide facilities for the residents to get building permits even if their houses are already built”.27 Instead of giving fines to people that build outside regulations, according to Mr. Abdellatif Brini of Tangier’s Urban Agency28 some local governments and municipalities (Commune-Mairie) have a series of 5-6 variations of house plans and are selling them out “at a symbolic price”, in order to encourage the population to regularize their condition.29

This encouraged process of regularization and the different mechanisms for restructuring have resulted in a permanent condition, an essential component in the production of space that could be considered the main social housing programme in Tangier. This programme involves private investment in the provision of homes; a procedure elsewhere considered a positive formula and that represents the less expensive option for the state.

19 Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix- Marseille University, 2006.

20 Ibid. p. 204

21 Minimal land subdivision in rural centres was re- duced from 1 hectare to 300 sqm. (data from Agence Urbaine).

22 Going back to the issue of ensuring circulation, when asked for the main reason why they were trying so hard to halt the expansion of the city, Mr. Abdellatif Brini explained that it was to prevent increasing traffic congestion towards the central city. “It is to take the pressure off the city, in terms of transportation, and the environment … You have seen the topography in the outskirts of Tangier, it’s very hilly, so in the end it turns out very expensive to introduce infrastructure!” Author’s translation from the French for all quotations of this conversation.

23 Programme des Nations Unies pour les Etablis- sements Humains – ONU-HABITAT Mission d’appui. Evaluation du programme national «Villes sans Bidonvilles» Rabat, 2011. [Accessed 24 May 2013]; Available from http://www.unhabitat.org/downloads/ docs/11592_4_594598.pdf

24 As the geographer Jullien Le Tellier points out “more responsibilities are left to the inhabitants: pur- chase of plots, building process and participation in restructuring costs. In the end, doesn’t non-regulatory housing turn out to be relatively cheaper for the state than the slums, which could explain the tolerance towards this type of habitat? Le Tellier J., Les Recom- positions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006. p. 195

25 Ibid.

26 “Mise à niveau urbaine de Haoumat Chouk” powepoint presentation of the project put together by the Wilaya de Tanger, the Ministere de l’Habitat, the Holding Al Omrane, the Commune Tanger Ville, Associations des habitants, Fondation Tanger Medina, Association DARNA and the Atelier d’Architecture Hanae Bekkari.

27 Restructuring operation of the Korret Sbaâ neighbourhood in Tétouan conducted by the Agence Urbaine, mentioned in Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006. p. 405

28 Meeting held on 28th February 2013 with the Chargé de Mission of Tangier’s Agence Urbaine, Mr. Abdellatif Brini

29 “In 2001, only one out of ten built terrains of the [Korret Sbaâ] neighbourhood was registered and on the cadastre. More than 80% of the population, however, declared being owners during the studies before the restructuring works. The restructuring plan launched in 2003 seeks to facilitate the procedures for registering property in land conservation and reporting to the Ministry of Finance” Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006. p. 393

Political territories and territorial policies

Political territories

“Discipline is centripetal, while security is centrifugal; discipline seeks to regulate everything while security seeks to regulate as little as possible, and, rather, to enable, as it is, indeed, laissez faire; discipline is isolating, working on measures of segmentation, while security seeks to incorporate, and to distribute more widely”.

Elden, S., Governmentality, calculation, territory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2007, volume 25, pages 562-580. p. 565

31 Première phase du projet Korret Sbaâ, avril 2001, p. 2

32 As the names of the main organisations deal-

ing with the issue: ANHI : Agence nationale de (lutte contre) l’habitat insalubre (établissement public du ministère de l’Habitat) and PARHI : Programme natio- nal d’action pour la résorption de l’habitat insalubre

33 Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix- Marseille University, 2006. p. 187

34 Foucault, M., Senellart, M., Ewald, F., & Fontana, A. Security, territory, population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan. 2007. p. 23.

35 “Moqqadem is a “local authority agent, based on proximity, under the responsibility of a caïd (Ministry of Interior). In urban areas, it is official and its respon- sibilities cover a neighborhood. Its role is to moni-

tor, control and report to the caïd”. Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006. p. 15

36 Wali is a “governor of province / prefecture capital of region (Ministry of Interior)” Ibid. p. 16.

37 Foucault, M., Senellart, M., Ewald, F., Fontana, A. Security, territory, population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan. 2007. p. 59.

38 Elden, S., Governmentality, calculation, territory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2007, volume 25, pages 562-580. p. 564

39 Meeting held on 28th February 2013 with the Chargé de Mission of Tangier’s Agence Urbaine, Mr. Abdellatif Brini

40 “The inclusion of non-regulatory neighbourhoods is illustrated by the creation of public schools; Quranic schools in these newly integrated neighbourhoods close and are gradually replaced by private structures that host the younger children (kindergartens)”. Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix- Marseille University, 2006. p. 395

41 We could consider in this case the coexistence

of procedures of “normation” and “normalisation”. Foucault, M., Senellart, M., Ewald, F., Fontana, A. Security, territory, population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan. 2007. p. 55-63.

42 Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix- Marseille University, 2006

43 Veolia Environnement via its holding company Veolia Services à l’Environnement Maroc (in charge of Moroccan water, wastewater and electricity services, and operated by concession companies Redal and Amendis)

44 De Miras, C., Le Tellier J., Gouvernance urbaine et accès à l’eau potable au Maroc. Partenariat Public- privé à Casablanca et Tanger-Tétouan, L’harmattan, Villes et entreprises, Paris, 2005.

45 “If the parcelling of parent titles such as carried out by the owners are usually illegal, most are still backed by the municipality that legalises the selling acts” Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006. p. 393.

46 Mr. Abdellatif Brini said that it puts the Directrice de L’Agence Urbaine at the same level of power as the Governeur.

47 Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix- Marseille University, 2006. p. 403.

48 Elden, S., Governmentality, calculation, territory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2007, volume 25, pages 562-580. p. 565

49 Foucault, M., Senellart, M., Ewald, F., Fontana, A. Security, territory, population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan. 2007. p. 29.

50 Ibid. p. 66.

51 Presentation on 28th February 2013 given by the Chargé de Mission of Tangier’s Agence Urbaine, Mr. Abdellatif Brini

52 “Mise à niveau urbaine de Haoumat Chouk”

powepoint presentation of the project put together by the Wilaya de Tanger, the Ministere de l’Habitat, the Holding Al Omrane, the Commune Tanger Ville, Associations des habitants, Fondation Tanger Medina, Association DARNA and the Atelier d’Architecture Hanae Bekkari.

53 It is an interesting coincidence, the opposition between the white city and the red city (the city in “sin”). One could almost extract a moralising attitude from the entire restructuring procedure.

As Stuart Elden exposes, Foucault identified the strategies through which power extends its domains, ignoring differences and assimilating them into an apparent regulatory entity. The case of NRH in Tangier and its restructuring programmes are a paradigmatic case which shows a way in which the territory is managed through territorial scopes. In front of a condition that appears to be outside from political control, various aspects from the restructuring procedures evidence an attempt of extending the governance into otherwise ungoverned areas.

The different terminologies by which the phenomena is addressed within the Moroccan society are very eloquent in containing in themselves the particular attitudes that are then engaged towards them: quartier marginalisé31, habitat insalubre32 are the most common, but also habitat sous-équipé, bidonville, zone de baraques, habitat non réglementaire, habitat dégradé, habitat spontané, habitat précaire, habitat anarchique, habitat clandestin, habitat marginal, quartier sous-intégré, quartier sous-équipé, quartier non-réglementaire(…).33 The emphasis is either put on its structural qualities or on its relation to the normal city, against which these neighbourhoods appear as anarchic. The restructuring processes themselves also take names worth mentioning: mise à niveau, restructuration, résorption, réaménagement, normalization (upgrading, restructuring, absorption, redevelopment, normalisation).

Even though the non regulatory neighbourhoods differ in their state of isolation, origin of the migrant population, and level of equipment, among others, the way of approaching their incorporation to the urban reality is to encircle them under a single definition that allows them to be identifiable and thus dealt with (as Foucault would name it, it is the appearance of a case):

“(…) one of the fundamental elements in this deployment of mechanisms of security, that is to say, not yet the appearance of a notion of milieu, but the appearance of a project, a political technique that will be addressed to the milieu”.34

It should be noted that the present methods of dealing with the illegal housing issue is through a mechanism of “inclusion”, since the state seeks to incorporate them as part of the urban realm. A different kind on procedure of dealing with these places could erase all these subtleties. However, the “inclusion” paradigm considers taking into account these particularities and brings them into the system: adoules, mocqadems35 and walis36 are respected in their distinct importance and are taken as a working part of the apparatus, as part of the assemblage, “finding support in the reality of the phenomenon, and instead of trying to prevent it, making other elements of reality function in relation to it, in such a way that the phenomenon is canceled out, as it were”.37 In this way, identity is not opposed to but an element contributing to the construction of the new territory. As Elden clarifies, when referring to Foucault’s differentiation between safety and security, “(…) mechanisms shift from exclusion to inclusion, to sending the victims outside the bounds of the polity, to a mechanism for spatial partition that allows them to be contained within”38 and by doing this (as was openly commented by Tangier’s Urban Agency Head of Mission, Mr. Abdellatif Brini) putting themselves in a situation where they are now obliged to consider them as part of the city.39 This obligation entails the “levelling” of these neighbourhoods in terms of infrastructure and services.40

This new urban territory now has to comply with the same regulations and be served equally to the rest of the city, otherwise it is not acceptable. The normal condition is seen as an objective to be attained, thus normalisation procedures need to be carried out.41 These normalisation procedures, interestingly enough, have a strong emphasis on the incorporation of infrastructure. Roads, sewage, electricity, water and waste collection are the means to achieve the desired absorption of otherwise marginalised neighbourhoods into the formal city. The geographer Jullien Le Tellier even carries out a qualitative categorisation of the neighbourhoods according to their various conditions of inclusion and exclusion in relation to the city, and of their susceptibility to being included according to their various topographic, social, and location particularities, among others.42

In terms of provision of services, Veolia Environnement43 together with the Al Omrane Group are the new messiahs of the inclusion: their mission is seen as the only means of “redemption” of societies that look up to them as the providers of a droit de cité (right to the city). The population rightly regards these operations as a permanent validation from society, and it is not so much the opening of standpipes but the home water connection which is significant of a real right of citizenship”.44

This is a very key subject, since the authorities are careful to not give the “droit de cité” to anyone: they cannot send a wrong message, as if anyone who takes matters into their own hands and builds illegally, anywhere, will eventually be granted property and “habitation” rights. A legal framework has thus been constructed in order to regulate the requirements for the inclusion of a determined housing type to the legal boundaries of the city. This framework is interesting as it accepts as valid proofs or evidences credentials such as “actes adoulaires”, purchasing certificates given by adoules (traditional notaries that operate through elderly male witnesses) that can now be legalised as proof of having bought a terrain.45 The same is true regarding construction permits. What is important to note is that this is not only an encouraged process of normation, but also a post-facto one.

It is interesting to interrogate the role of the “Agence Urbaine” in Morocco: Le Tellier considers the creation of the agency as an act of regaining central power46, “centralising” the decision-making and re-territorialising the region: “The recent creation of urban agencies in Morocco can be interpreted as a form of recentralization of power. It is for the State, a way to control municipalities and interfere in local affairs, especially in terms of urban planning and development”.47 In this sense, the introduction of infrastructure is a crucial factor to be analysed: one can’t only see it as a generous action by the state. These populations were already functioning without it. Circulation infrastructure is, in fact, a way of regaining (or re-reigning) a territory that was otherwise considered to be completely out of control. This is again a matter of security: referring to Foucault’s Security, Territory, Population, Elden notices how “while discipline operates through the enclosure and circumscription of space, security requires the opening up and release of spaces, to enable circulation and passage”.48

The modifications mentioned beforehand regarding changes in rural regulations and possible extensions of the urban limit, are an example of “(…) how the territorial sovereign became an architect of the disciplined space, but also, and almost at the same time, the regulator of a milieu, which involved not so much establishing limits and frontiers, or fixing locations, as, above all and essentially, making possible, guaranteeing, and ensuring circulations”.49 Mr. Abdellatif Brini also commented on a process of demarcation and recognition of each one of the neighbourhoods having needed to be carried out, which again responds to “the delimitation of phenomena within acceptable limits, rather than the imposition of a law that says no to them. So mechanisms of security are not put to work on the sovereign-subjects axis or in the form of the prohibition”.50 Infrastructure can then be understood as a deployment of security, a way of procuring sovereignty over a risky population.

The resulting built space of the non-regulated phenomena and its gradual incorporation into the urban fabric is evidence the mechanisms of territoriality being deployed. To give an example, the Agence Urbaine directed what was called an “opération-modèle de restructuration” in the Monghoha neighbourhood, and the state procedures over the neighbourhood to be “restructured” are very evidently marked through a territorialisation mark, a signature: the white painting of the buildings.51 The same can be seen on the urban upgrading of the Haoumat Chouk neighbourhood.52 The painting of the facades is a way of incorporating that part to Tangier, the “white city”.53

Territorial policies: territorialisation

The concept that is constantly present and underlying all these conflicts is territoriality. Urban policies have proven to understand the region from a more abstract perspective, leaving aside the particular physical realities and the mechanisms through which they were produced. The problem of the poor understanding of the territory (which is an inherently unequal space) and its confusion with territoriality (that attempts an homogenisation of it) is at the base of the perpetuation of urban conflicts and tensions.

To take this even further, actions of de-territorialisation and re-territorialisation are constantly mentioned in regards to territory. This displacement procedure would allegedly explain the processes taking place in the globalised world, where territory is subject to a constant redefinition beyond its bounds and suggesting that it is affected by thoughts and meanings originated from different locations. The peripheral areas of Tangier are subject to de-territorialisation and re-territorialisation procedures54, through which the central government attempts to redefine their existence and status. However, a more sensible approach would be to recognise them as a territory in themselves, contiguous but different from the pre-existing Tangier, since they have been produced through very different political, economic and social processes, and are built over different topographic and terrain conditions. These particularities press the importance of re-thinking what territory means and what significances that should convey to the urban discussion.

How do we define a territory? The idea of territory is a multi-layered concept, and while it commonly defines a potential area or domain, its definition varies according to the field of study.

Territory comes from the Latin word territorium, formed by the root terra (earth, land) and of the suffix orium (denoting place). According to Stuart Elden,”territorium is an extremely rare term in classical Latin that becomes common in the Middle Ages. The standard definition is the land belonging to a town or another entity such as a religious order”.55 The notion emerged mainly as a political-administrative concept, and has since been stretched into other (political-economic and political-strategic) domains.

Elden argues that territory is rarely theorised or defined in itself, and is normally substituted with other notions which could be close or adjacent but which are not identical to territory. “Where it is defined, territory is either assumed to be a relation that can be understood as an outcome of territoriality, or simply as a bounded space”.56 Most definitions of territory do slide into either space or territoriality very easily, making it hard to distinguish a straightforward understanding of the term.

The first confusion has to do with the proximity with the concept of space. The simplest, more basic and unfettered way of looking at the place where things move and exist seems to be the obvious base upon which to construct the idea of territory. This is a reasonable approach, considering that it attempts to grasp the physical reality of it, endowing it with a sensitive quality that can be perceived and understood. However, space lacks the depth of territory, and in order to approach territory to space, the term needs to be invested with additional dimensions. Claude Raffestin for example reflects on territory as being a space transformed by human work,57 and Edward Soja comments on territory as space that can be divided and traded as a commodity.58 Raffestin even says that “territory is generated from space, through the actions of an actor, who “territorializes” space”.59 When assimilated as space, territory loses the potential active qualities and resonances it may have and is flattened to signify only the surface that holds space.

The confusion with territoriality is even more frequent. It is true that territory is something that is being produced and not a fixed entity. In this sense, it is something which is always in a state of production; it is in movement and to record its movement means to record the territory. It can then be considered an action which could comprise movements of territorialisation. However, this does not mean that territory is territorialisation, even though most definitions of territory resort to it. Robert Sack’s view on territories requiring “constant effort to establish and maintain”60 is an example of this transposition of territory into territorialisation. Deleuze and Guattari are closer to an dynamic understanding of the concept when they say that “the territory is in fact an act that affects milieus and rhythms, that “territorializes” them. The territory is the product of a territorialization of milieus and rhythms”.61 Despite this proximity, Elden explains how even though territory is in fact one of the products of territorialisation, it still needs a definition of its own since it is “logically prior to territoriality, even if existentially second”.62

54 We could describe a restructuring procedure as

a re-territorialisation in itself: it attempts to evenly transform the existing spatial and social configurations of neighbourhoods that were born through various and particular rural migration processes, and have a local internal functioning (proper to the Rifains, Casa- ouis, Rabelais, Arabic or Muslim cultures, to name just a few).

55 Elden, S., Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography. 34, 799-817. 2010. [Accessed 24 May 2013]; Available from: http://dro.dur.ac.uk/6850/1/6850.pdf. p. 10.

56 Ibid. p. 1.

57 Raffestin C., Ecogénèse territoriale et territorialité, in Auriac F. et Brunet R. (eds.), Espaces, jeux et enjeux, Paris: Fayard, p. 173-185. 1986.

58 Soja, E. W. The Political Organization of Space, Commission on College Geography Resource Paper No 8, Washington: Association of American Geographers, 1971.

59 Raffestin cited in Elden, S., Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography. 34, 799-817. 2010. [Accessed 24 May 2013]; Available from: http://dro.dur.ac.uk/6850/1/6850.pdf. p. 5.

60 Sack, R. D. Human Territoriality: Its Theory and History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1986

61 Deleuze, G., Guattari, F., A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brain Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988. p. 314.

62 Elden, S., Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography. 34, 799-817. 2010. [Accessed 24 May 2013]; Available from: http://dro.dur.ac.uk/6850/1/6850.pdf. p. 6.

The determinateness of territory: the role of physical geography in the definitions of territory

63 Scholte, J. A., Globalisation: A Critical Introduc- tion, Houndmills: Macmillan. 2000., cited in Elden, S., 2005. Missing the point: globalization, deterritorializa- tion and the space of the world. Blackwell.

64 Elden, S., Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography. 34, 799-817. 2010. [Accessed

24 May 2013]; Available from: http://dro.dur.ac.uk/6850/1/6850.pdf. p. 16.

65 Elden, S., 2005. Missing the point: globalization, deterritorialization and the space of the world. Black- well. p. 18.

66 Ibid. p. 1-2.

67 The architect Hanae Bekkari for example supports the idea that the disregard of the physical condi- tions in the planning and development of Tangier is determinant to explain it current urban situation: “In my view, the three base maps supporting any urban action or architectural action in Tangier are the Topographic Plan (plan topographique), the Geoech- nical map (carte geotechnique) and the “Carte des Vestiges”. H. Tanger Post Internationale, article in Urban generations : post-colonial cities / ed. by David Richards, Taoufik Agoumy, Taeib Belghazi. – Rabat : Faculty of Letters of Rabat, 2005. – 471 p. : ill., krt. ; 24 cm. – (Publications de la Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Rabat Série: Colloques et sémi- naires, ISSN 1113-0377 ; 126). p. 274.

68 In this sense margins refers to the limits of a certain focus. Maps for example constantly avoid rep- resenting the areas outside the established limits.

69 Schmitt, C., Land and Sea [1942, 1954], trans. Simona Draghici (Washington, DC: Plutarch Press, 1997), p. XIV (foreword).

Despite the previous discussion, there is something about the word territory that suggests the existence of a down-to-earth entity. Notions of spatiality, materiality, and physicality would need to prevail in such an idea. However, when looking at the primary definitions of territory and its contemporary derivation to notions of de-territorialisation, there is something which is constantly being left aside: territory itself. One could argue that from an original deepening of the concept through understandings of its potential scope (particularly in political theory, social sciences and philosophy) the term has increasingly lost attachment to the ground it is subject to.

It is clear that qualifying a certain territory only by its natural specificity is rendering the term short. However, bringing the political, economic and technical notions of territory back down into a closer relation to the actual land conditions or terrain they are being drawn over will necessarily enrich these understandings by adding a sort of ground layer to them. Each way of understanding a territory can be then read as a moving phenomenon occurring over a transforming physical canvas, and the superposition of all these layers results in a moving palimpsestic notion of territory. Despite the consensus on territory being an almost supra territorial concept in the globalized era63, I argue following Elden that physical geography is an unavoidable condition for the definition of territory.

Elden himself first suggests a return to geographic dependence by arguing that it is fundamental when attempting to explain the human occupation of the territory:

“To concentrate on the political-economic risks reducing territory to land; to emphasise the political-strategic blurs it with a sense of terrain. Recognising both, and seeing the development made possible by emergent political techniques allows us to understand territory as a distinctive mode of social/spatial organisation, one which is historically and geographically limited and dependent, rather than a biological drive or social need”.64

While the de-territorialisation (the removal of the ground component) from the classical definition of territory operates from a certain poetic about information technology, circulation and non-places, hypertext, ubiquity, real-time communication, decentralized network, etc. the fact is that all these notions are ultimately based on land or ground and have a connection to the physical territory. They flaunt a presumed immateriality, beautiful but utopian, for cables and antennas exist in reality and have a precise location and sense due to geography. Discussing Scholte’s argument of the existence of a trans-world simultaneity or instantaneity, Elden believes that “this does not escape the ‘logic’ of territory; rather it demonstrates the importance of the temporal to understandings of spatiality”.65

Disturbingly, “the predominance of “understandings of globalisation as de-territorialisation, which claim that territory no longer occupies the foundational geographical place” have “even led to the suggestion that geography is less significant, or even that spatial considerations are not important at all”.66 My argument seeks to stress the importance of territory being a distinctive mode of spatial organisation, supporting the idea that territories have a physical manifestation of an immanent configuration that should be primary within any critical reading. This physical manifestation is even clearer and easier to abstract when looking at fast occurring urban phenomena such as the peripheral expansions of cities, where repetition and magnitude give enough samples to identify a pattern. As we saw in the previous chapter, the recent urban sprawl of the city of Tangier is not the sole product of a particular political-economic situation, but an explicit form of territorial construction.

Rather than territorialisation practices, what should prevail is an insistence on the territory, a territorisation. Urban programmes and structuring processes attempt to keep enlarging the urban, as if prolonging roads and pipes was the only approach possible. However, an emphasis into making the most of their particularities would be more appropriate67, and following this idea, the creation of a local governance entity would make sense. Looking at Tangier (and other sprawling cities) from this perspective would allow understanding that in some way, it was not the city that sprawled, but rather it was the rural areas that approached the city and flourished besides it. This shift of perspective regarding the growth of territories in the margins68 would be beneficial when addressing their urban circumstances. The expansion of non regulatory housing is in fact re-producing the territory, pushing the urban boundaries from the outside, inverting centre and border conditions. In the same way as in the foreword to the 1997 edition of Land and Sea, Simona Draghici explains Carl Schmitt’s concept of spatial revolution as being a representational shift of boundaries69, these new territories deserve a revolution themselves: the account for their unique logic of production of the territory.

Bibliography

Amzil, L., Debbi, F., and Le Tellier, J. La Mobilité Urbaine dans L’Agglomération de Tanger: Evolutions et Perspectives. Sophia Antipolis: Plan Bleu, 2009.

Bekkari, H. Tanger Post Internationale, article in Urban generations : post-colonial cities / ed. by David Richards, Taoufik Agoumy, Taeib Belghazi. – Rabat : Faculty of Letters of Rabat, 2005. – 471 p. : ill., krt. ; 24 cm. – (Publications de la Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Rabat Série: Colloques et séminaires, ISSN 1113-0377 ; 126)

Elden, S., 2005. Missing the point: globalization, deterritorialization and the space of the world. Blackwell. Available at: http://dro.dur.ac.uk/1175/1/1175.pdf

Elden, S., 2007. Governmentality, calculation, territory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2007, volume 25, pages 562-580

Elden, S., Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography. 34, 799-817. 2010. ; Available from: http://dro.dur.ac.uk/6850/1/6850.pdf

de Haas, Hein (2005) International migration and regional development in Morocco. Workshop New Moroccan Migrations, Institute of Development Studies, Sussex Centre for Migration Research, University of Sussex, 13 July 2005.

Deleuze, G., Guattari, F., A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brain Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

Foucault, M., Senellart, M., Ewald, F., Fontana, A. Security, territory, population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan. 2007.

Haut commissariat au Plan et direction de la Statistique. Recensement général de la population et de l’habitat, ; Available from: [a href=”http://www.hcp.ma”]http://www.hcp.ma

Le Tellier J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, doctoral thesis of geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006.

Le Tellier, J., 2009 Relations sociales et lieux de sociabilité urbaine autour des bornes-fontaines publiques à Tanger (Maroc), in Les lieux de sociabilité urbaine dans la longue durée en Afrique, Fourchard Laurent, Goerg Odile, Gomez-Perez Muriel (éd.), Paris, L’Harmattan, Forthcoming.

L’immigration subsaharienne au Maroc / MGHARI, Mohamed, 2008, Euro-Mediterranean Consortium for Applied Research on International Migration (CARIM)

Raffestin, C., 1977. Paysage et territorialité. Cahiers de géographie de Quebec 21: 53-54.

Raffestin, C. Territoriality. A reflection of the discrepancies between the organization of space and individual liberty. International Political Science Review, 1984, vol. 5, no. 2, p.139-146

Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:4346

Raffestin C., Ecogénèse territoriale et territorialité, in Auriac F. et Brunet R. (eds.), Espaces, jeux et enjeux, Paris: Fayard, p. 173-185. 1986.

Raffestin C., Butler S. A., 2012. Space, territory, and territoriality. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30(1) 121 – 141

Hyunjin, K. The Study and Example of application for the Establishment of Cadastral Methodology in Morocco. TS 5K – Cadastral Projects. FIG Congress 2010 Facing the Challenges -Building the Capacity. Sydney, Australia, 11-16 April 2010. ; Available from http://www.fig.net/pub/fig2010/papers/ts05k\ts05k_kim_4150.pdf

Programme des Nations Unies pour les Etablissements Humains – ONU-HABITAT Mission d’appui. Evaluation du programme national “Villes sans Bidonvilles” Rabat, 2011. ; Available from http://www.unhabitat.org/downloads/docs/11592_4_594598.pdf

De Miras, C., Le Tellier J., Gouvernance urbaine et accès à l’eau potable au Maroc. Partenariat Public-privé à Casablanca et Tanger-Tétouan, L’harmattan, Villes et entreprises, Paris, 2005.

Soja, E. W. The Political Organization of Space, Commission on College Geography Resource Paper No 8, Washington: Association of American Geographers, 1971.

Sack, R. D. Human Territoriality: Its Theory and History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1986

Scholte, J. A., Globalisation: A Critical Introduction, Houndmills: Macmillan. 2000.

Schmitt, C., Land and Sea [1942, 1954], trans. Simona Draghici (Washington, DC: Plutarch Press, 1997), p. XIV (foreword).

Image references

[1] Nicole Rochette, 2013.

[2] [3] Built upon information found in Le Tellier

J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006

[4] University of Texas Libraries available at http:// www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/ams/morocco_city_ plans/

[5] Tangier unit group work, 2013.

[6] View of Aouama neighbourhood available at http://www.tripmondo.com/morocco/region-de- tanger-tetouan/aouama/

[7] Nicole Rochette, 2013.

[8] [9]Built upon information found in Le Tellier

J., Les Recompositions territoriales dans le Maroc du Nord, Doctoral Thesis of Geography, Aix-Marseille University, 2006

[10] [11] [12] Nicole Rochette, 2013.

[13] Atlas of Morocco, available at http://www. hoeckmann.de/karten/afrika/marokko/index-en. htm